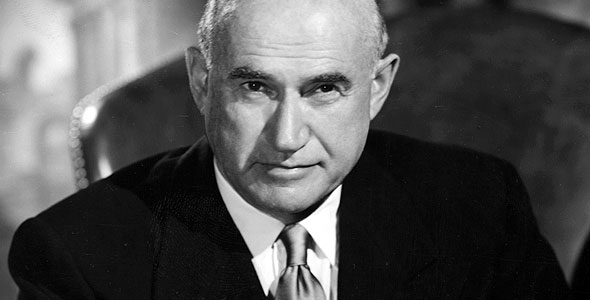

Back in the late 1980s, A. Scott Berg gave film fans the definitive biography of pioneering film producer Samuel Goldwyn.

While reading the William Fox biography, I learned that Sam Goldwyn had been forced out of Goldwyn Productions, which he formed with the Selwyns. The studio had been named after their names: Goldfish and Selwyn. Until that point, I had always assumed he had been involved with the leadership of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. This wasn’t the first film company that the producer had been forced out of. No, he was also forced out of the Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company (co-founded with Lasky and Cecille B. DeMille) that would later merge with Adolph Zukor’s Famous Players. That company is now known as Paramount Pictures.

Wanting to stay in the industry, the producer would start up Samuel Goldwyn Productions. In doing so, he would become one of the biggest independent producers. Of course, he would turn to the likes of United Artists, RKO, and others in order to distribute films.

Goldwyn would produce just north of eight films during his lifetime. The Oscars would only award one of those films as Best Picture: The Best Years of Our Lives. There were other films over the years to be nominated but The Best Years of Our Lives was the only one to take the crown. But for all the films that would go onto be nominated for an Academy Award, there were indeed the films that got away. The biggest film of all was The Diary of Anne Frank. While the producer didn’t have anything to do with An American in Paris, the Oscar winner featured the same piece of music that George Balanchine’s choreography had been ordered to be cut from The Goldwyn Follies in 1937.

He wasn’t on the same level as Columbia’s dictatorial Harry Cohn although Goldwyn certainly did have issues with those working under contract. William Wyler wouldn’t always take his assignments and would go onto be suspended. Among actors, only Gary Cooper and David Niven would give him their gratitude for giving them their start in Hollywood.

Like other moguls of his era, he was a Republican. In the late 1930s, he sat in on an off-the-record talk with Joseph P. Kennedy, Sr. It was a very uncomfortable conversation for all the Jewish moguls and such who were sitting in the audience. Put it this way: the anti-Semitism in Kennedy’s dialogue was enough to lead Goldwyn to support Richard Nixon’s presidential campaign in 1960. Even to this day, there is much shame placed upon the isolationists who wanted nothing to do with World War 2 or the plight of Jews in Europe.

The book runs just over 500 pages before getting into notes and the bibliography. It’s well-researched with numerous interviews and full access to the mogul’s archive. As noted in the acknowledgments, it was Sam Goldwyn’s idea to have a biography written about him. However, he didn’t want to be alive when it was published. Given their relationship, a book could easily be written about Goldwyn and Oscar-winning filmmaker William Wyler. That said, this one isn’t bad at all.

In the biography, Berg presents an all-around portrait of Goldwyn as a pioneering filmmaker and as a father. If you’re looking to learn about the early moguls and producers, Goldwyn is a must for your bookcase or Kindle.