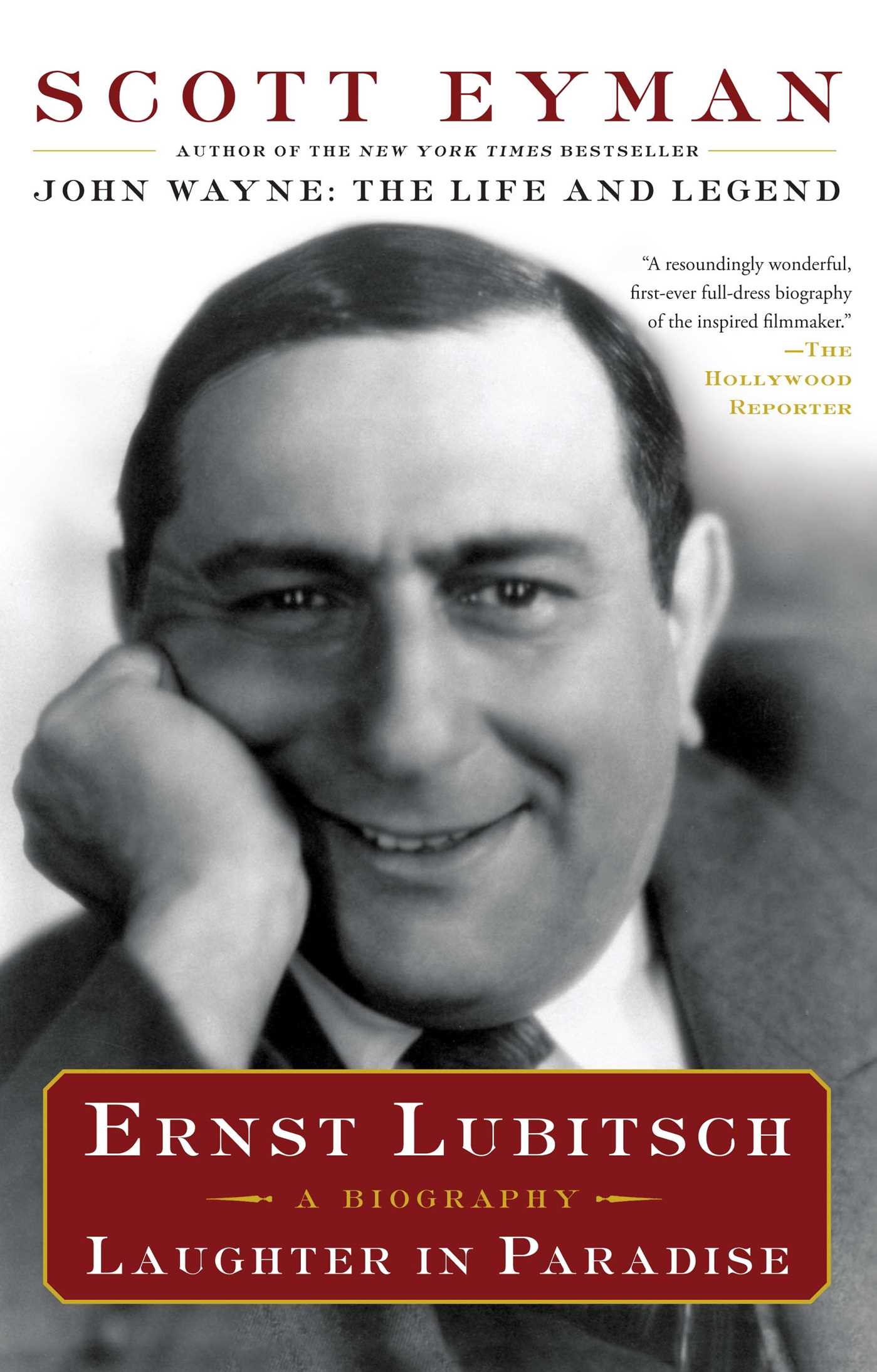

Ernst Lubitsch: Laughter in Paradise, written by film historian Scott Eyman, is the definitive biography of the To Be or Not To Be filmmaker.

The first thing I took away in reading Eyman’s biography is that Lubitsch was considered to be “The Griffith of Europe.” Unfortunately, the filmmaker also emulated Griffith in more ways than one. This includes, sadly, wearing blackface as one of his characters. It’s sad and unfortunate because he was one of the greatest filmmakers of his era. Outside of maybe film scholars, Lubitsch doesn’t have the same recognition as some his contemporaries like Cecil B. DeMille. Though to be fair, I only know him because of Ninotchka, The Shop Around the Corner, and To Be or Not To Be.

Lubitsch would act out scenes on set for the actors prior to shooting. Some actors were able to benefit from his directing process. Others weren’t. For Jack Benny, Lubitsch would be the best director that ever directed him in anything. For Greta Garbo, Ninotchka became her greatest film. After twelve screen dramas, the film would mark her first comedy. The film came at a time when studios were still transitioning from silent to sound.

Lubitsch’s heart issues put a pause in his career in the 1940s. When he did set out to direct a film in 1947, it would be his last time on a movie set for he would end up dying of a heart attack that year. His death came in the same year in which he received an honorary Oscar to honor his quarter-century or so of filmmaking.

What we know as The Lubitsch Touch owes a debt to Max Reinhardt as Eyman writes:

Indeed, with a few exceptions, for the rest of his career, Ernst would use Max Reinhardt’s unified blending of script, setting, and performance, even on material generally thought too insubstantial to warrant such painstaking care. The result would be a foundation of grave, methodical intent supporting a blithe, carefree, beautifully textured surface structure. In time, this construct would come to be known as “The Lubitsch Touch.”

Lubitsch took the secret to his grave according to writer-director Billy Wilder. Wilder co-wrote a few films for Lubitsch so he would know. Lubitsch’s legacy was able to live on by way of a spiritual successor in Wilder. Upon learning that he received the AFI Lifetime Achivement Award, Wilder joked that he only got it because Lubitsch was dead.

Scott Eyman writes a thoroughly complete examination of Ernst Lubitsch in terms of both filmography and his life. It’s a definitive portrait in this way. There will never be another Ernst Lubitsch as the German-born filmmaker was one of a kind.