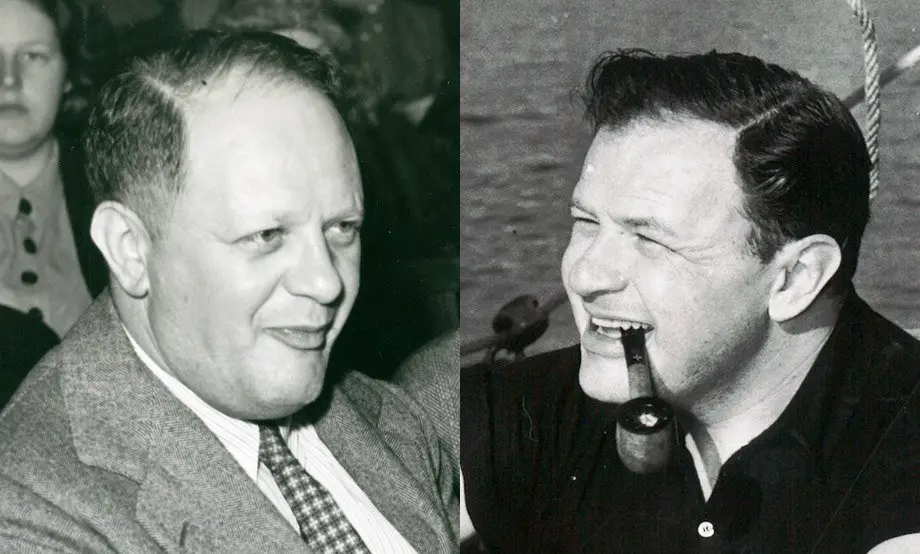

Sydney Ladensohn Stern’s The Brothers Mankiewicz: Hope, Heartbreak, and Hollywood Classics is a solid read and works as a dual biography.

I immediately changed up my quarantine reading list when Netflix issued the first teaser trailer of Mank on October 8. Going into that day, my plan had been to start on Scott Eyman’s biography of Cary Grant in hopes of finishing in time for its October 20th release. Alas, The Brothers Mankiewicz took immediate priority. Not only for insight for whenever I watch Mank but also rewatches and first viewings of Mankiewicz films.

The spring of 1978 saw the release of two Mankiewicz biographies on each brother. Richard Meryman penned a biography on Herman while the other one is written about Joe by Kenneth Geist. These two books are certainly important resources and The Brothers Mankiewicz also adds on to their legacy. In writing the book, Stern had access to all of the Joseph L. Mankiewicz material still in Rosemary Mankiewicz’s possession. This helps to form a clearer picture of who the younger Mankiewicz brother was as a person. In moving from Los Angeles to New York, a Bekins moving van caught fire and Hollywood history would be lost forever.

Together, Herman and Joseph Mankiewicz combined to write, direct, and produce 150 films. Among these are some of the greatest films in cinematic history. Among them are Citizen Kane, All About Eve, and yes, even the Marx Brothers. When they were starting out in the industry, producers contributed to story ideas but didn’t get writing credit on their films. This changed throughout their time in Hollywood. At one time, the Screen Writers Guild would not allow producers to have any writing credit. This is why Joe does not have writing credits on pictures he produced.

Both brothers had their eye on what was going on overseas. While Joseph Mankiewicz was on the committee that financed an Jewish anti-Nazi spy ring, Herman penned the script for Mad Dog of Europe. Unfortunately, none of the studios wanted to touch it. Knowing Warner Brothers at the time, you would have thought they would produce the film! Much of this certainly has to do with the power of the Code censors and how valuable the European market was to the studios. After a while, it didn’t matter because Herman’s films ended up being banned in Germany. The film never got made and producer A Rosen published the script as a novel under Albert Nesor. As far as I can tell, it’s currently out of print.

Stern’s book would be incomplete without a mention of Pauline Kael or her essay on Citizen Kane. One of the greatest films of all time, director and co-writer Orson Welles would often embellish the truth when it came to the film’s origin. When it originally came time for awarding screen credit, Welles didn’t want to give Mankiewicz any credit at all. There was a fight over the writing credits and it got messy. In correspondence to Alexander Woollcott, Herman wrote that “the conception of the story, the plot, the characters, the manner of telling the story and about 99 per cent of the words” were his “exclusive creations.”

As for Kael’s comments on Citizen Kane, Stern writes:

Most members of the general moviegoing, New Yorker-reading public were oblivious to the fact that Kael’s story of the film’s creation was a tendentious account owning more to her professional disagreement with fellow film critics than to any real desire to set the record straight on that particular film.

There’s a lot more to the story but I’m already curious to see how Mank the film depicts the real-life events.

The origin of Rosebud the sled dates back to when Herman’s own childhood bicycle was stolen. Some things do not leave you and Herman would draw on those experiences in writing the script. Moreover, the film’s sled was named for 1914 Kentucky Derby winner Old Rosebud.

More than just Citizen Kane, there are other films discussed here. All About Eve, which won Joe his second pair of Oscars for directing and screening, is discussed. I’ll be watching the film for the first time very soon.

Another section that is just as interesting is all the drama surrounding Cleopatra. If you think there’s drama in Patty Jenkins directing Gal Gadot as the former Egyptian queen, you might want to read up on the film starring Elizabeth Taylor. When producer Walter Wanger first approached Joe, his idea was a “$5 million picture starring Cary Grant as Julius Caesar, Burt Lancaster, as Mark Antony, and either Sophia Loren or Audrey Hepburn as Cleopatra.” Joe initially passed on the idea so Wanger turned and sold it to Fox. Fate had another thing in store after Rouben Mamoulian quit.

On top of their films, there is also their personal lives. While Joe married three different women, he also had a number of affairs throughout his life. Among them where some well known actresses. It was enough Chris referred to his father’s treatment of Rosa as “gas lighting.” Similarly, Tom’s experience with his mother led to a “lifelong pattern of gravitating toward troubled actresses.” Stern goes into detail on their personal lives. I’m not going to get into those details here but the book is a solid read.