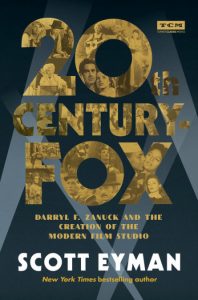

Film historian and bestselling author Scott Eyman has done it again with 20th Century-Fox: Darryl F. Zanuck and the Creation of the Modern Studio.

The story of the Hollywood studio can now be told after an era came to an end in 2020. If you didn’t read Vanda Krefft‘s brilliant biography on William Fox, Eyman sums up his life, the Fox Film Corporation, and his legal troubles. Zanuck really doesn’t come into the book’s picture until page 74. There’s a brief introduction and then Eyman starts the book around the time Fox purchased Loew’s in the late 1920s. But still, I highly recommend reading The Man Who Made the Movies if you want to really know the man that gave the Fox brand his name.

One thing to know is that this is a pandemic book. It’s certainly much shorter than a lot of the Scott Eyman books I’ve read during the pandemic. The book also comes in at a smaller page count than Hank and Jim. But again, it’s a pandemic book so many libraries were closed. This essentially means that Eyman is working from materials he already has on hand or whatever he can get from other film historians. When you’re a writer and lose access to the important film history libraries, it basically means just sitting around or figuring out how to write a book. For what it’s worth, Eyman makes the best of the situation. It’s really all anybody can do right now.

Working for the Mack Sennett studios (page 99) is where Zanuck learned things about movie-making that would stay with him:

“Sennett taught me two things about movie-making that I never forgot. One was that no matter how serious your picture is, no matter what momentous things you’re trying to say or show, the moment you forget to keep the action going, you’ve lost them. Put in anything, any old gag, a girl’s leg, a big explosion, a sudden scream, rather than let the audience’s mind wander, and that goes for any kind of film, whether you’re making Heartbreak House or Charley’s Aunt….Sennett knew that comedy is not words but action, and action is what movies are all about.”

As a studio mogul, Zanuck was considerably progressive for his era. Mind you, he was a liberal Republican in his politics but still. When it came to displaying race on screen, Zanuck wanted Black people displayed as real people and not a mockery. On page 151:

Fox’s showcasing of Fayard and Harold Nicholas, as well as producing movies such as Stormy Weather and No Way Out marks Darryl Zanuck as an early progressive in terms of the movie industry’s attitude toward race relations, which could be characterized as deeply hesitant until the subject became safe in the late 1950s.

Regarding the Hollywood blacklist, Zanuck was seen by some as behaving like a mentsch. On page 178:

Zanuck’s attitude toward the blacklist was sublimated fury, if only because someone was basically telling him who he could and could not hire.

When 20th Century-Fox chairman Spyros Skouras wanted Jules Dassin off the lot, it was Zanuck who went over to Dassin’s house. Zanuck gave Dassin a book and told him he was going to London and to get a screenplay and start shooting the most expensive scenes. The film turned out to be Night and the City. This is the same Zanuck who Dassin said could be “tough, so heartless.” And yet, he comes through in a big way when most moguls wouldn’t have given the blacklist a second thought!

Richard Zanuck, who would later produce Jaws, took over as president of 20th Century-Fox. This was in the early 1960s and he would resign before the end of the decade. While heading production, his goal was at least two road show films a year. Pretty ambitious but it is what it is. The first of which was The Sound of Music. This film would have been a very different film if his father had his way. Can you imagine Doris Day instead Julie Andrews? I can’t! Anyway, this quote from page 226 explains the younger Zanuck’s philosophy as production head:

“We’re going all out for the big, family-type show that I suppose you could call pure entertainment, I’m very much aware that what we do here is seen by millions of people around the world. My first responsibility is to the company I work for. but I also have a responsibility as a person and as a filmmaker to put on things of which I can be proud. I don’t intend to jeopardize that responsibility.”

It’s a quote that Eyman calls back later on some ten pages later once getting into the exploitation pictures. The elder Zanuck was no fan of Roger Ebert’s script. This kind of film was unbecoming for the studio. In part, it would help lead to the younger Zanuck being forced out. The Zanuck name may be synonymous with Fox but at some time, you move on.

Studios have changed in a big way since Zanuck got his start. They’re now operated by corporations. Some, like Disney, have gone onto acquire a number of other studios, rivals even. It used to be that the production head had all the power but these days, the power runs through producers, leading talent, and yes, even their agents. One of the few creative producers who has power in a way similar to Zanuck and Louis B. Mayer is Marvel’s Kevin Feige. Eyman notes on page 261 that the primary difference that separates them is that neither Zanuck or Mayer “would have tolerated their job being focused on seducing a currently hot producer or star so that they could earn more money than the studio head.”

As we all know, Ford v Ferrari would mark the end of an era. The final film from Fox. Or at least the old Fox. It closed up the studio’s storied history and is a film that the likes of Zanuck or Alan Ladd Jr. would have greenlit. The film would have been a great representative of the studio in any era. This speaks to the type of filmmaker that James Mangold is. One of the all-time best. The screenplay was excellent. The technical side of things were amazing. And now that the 20th Century-Fox brand is done, Eyman can finally tell the studio’s history and what a history it is.