Light & Magic is a 6-part documentary series that goes back into the archives to give us the deep history of Industrial Light & Magic (ILM).

The history of ILM cannot be told without George Lucas, John Dykstra, Ken Ralston, Richard Edlund, Dennis Muren, Robert Blalack, Joe Johnston, Phil Tippett, Steve Gawley, Lorne Peterson, and Paul Huston. It’s because of them that filmmaking would change as a result of a sci-fi film, Star Wars. Dennis Muren would also join the list of employees as a result of Phil Tippett reaching out. The list of people working at ILM reads like a who’s who of people working in visual effects. To think that none of this would happen without Star Wars. Visual effects would never again be the same. The game would change again in 1993 with the release of Jurassic Park. Everything about Hollywood filmmaking would change.

It’s interesting to look at how one thing leads to another. Warner Bros. pulled their support of Apocalypse Now (at the time, George Lucas was directing the film as a black comedy) when THX-1138 failed. This led Francis Ford Coppola to encourage the filmmaker to write a coming-of-age comedy. The result of this was American Graffiti. Cut to a few years later: Lucas is no longer working on his Vietnam War movie. He was now working on a movie inspired by Flash Gordon with no shortage of WWII dogfights. In truth, Star Wars was George Lucas’s Vietnam War film because he couldn’t get the rights to make a Flash Gordon movie. The rest is history.

One fascinating piece of information about Star Wars comes from then-modelmaker Joe Johnston. The Millennium Falcon‘s original design is closer to that of the Tantive IV. Lucas wanted a new design because the Falcon’s design was similar to that of a ship in Space: 1999. It would be fine for the blockade runner but not for Solo’s ship. The only things that came over from the original design were the cockpit and the circular sensor rectenna dish.

There’s no shortage of fascinating tidbits in this film. While there have been previous documentaries about ILM, this is as in-depth as it gets. Some of this won’t be new if you’ve seen those docs or even read the George Lucas biography written by Brian Jay Jones. There’s no telling just how much interview footage–present or archival–is on the cutting room floor. While ILM has won 16 Oscars for their work in visual effects, it should not come as a shock that the bigger focus is on Star Wars. After all, ILM wouldn’t exist without the blockbuster. The third episode starts with the theatrical release before moving onto The Empire Strikes Back. There’s even more fun that we learn in this episode, including the camera trickery with the Falcon jumping into hyperspace.

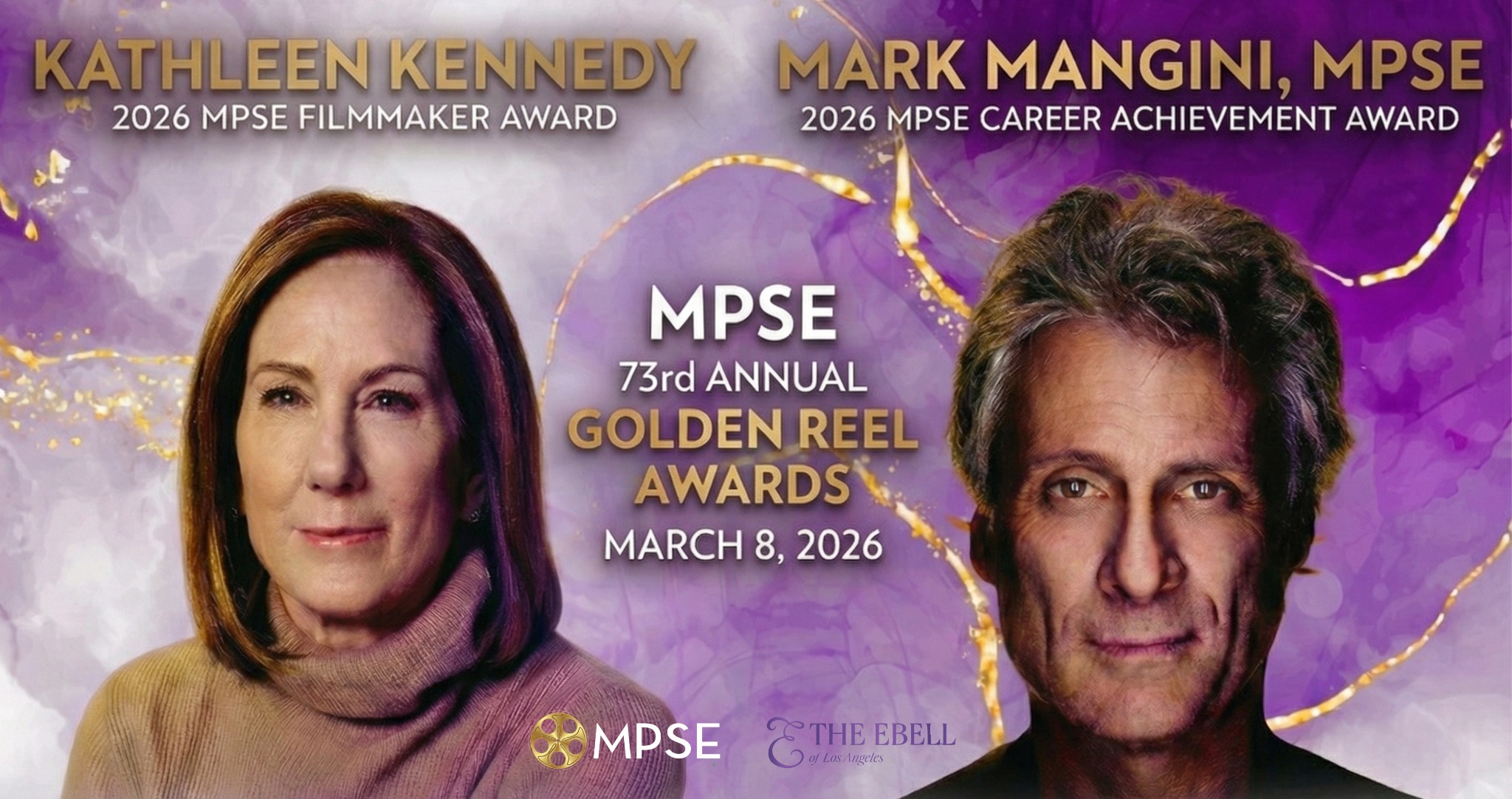

Return of the Jedi might be around the corner but ILM started becoming a work-for-hire company. This enabled ILM to work on numerous films including Raiders of the Lost Ark, Dragonslayer, Poltergeist, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, etc. The company became more than a division of Lucasfilm during the 1980s. It was becoming the go-to place for visual effects. The fourth episode finally sees Light & Magic move beyond Star Wars with a focus on the likes of Raiders of the Lost Ark and E.T. There are some aspects here that have previously been covered in the Laurent Bouzereau docs. Dennis Muren discusses his process when it comes to some of the visual effects shots in E.T. when it comes to getting the bikes flying off the ground. Steven Spielberg, Frank Marshall, and Kathleen Kennedy discuss their relationships with both Dennis and Richard.

Regarding VFX, Frank Marshall says that “each visual effects supervisor is like a mini-director.” It’s an interesting comparison.

Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan begins an era of ILM showing off what it can do digitally. Sequences in the film were done digitally rather than using practical effects. It’s also one of those films where ILM worked for other filmmakers because, again, Return of the Jedi would use 170 ILM employees on the film. Funny enough, we get a glimpse into the rehearsal process and there’s a moment where Phil Tippett is performing and dancing as Max Rebo, much to his wife’s surprise. If you look closely, per Ken Ralston, yogurt containers, wads of gum, and a shoe make up the Rebellion’s fleet. If it works, it works, right?

Every time a George Lucas film came along, ILM had to outdo themselves again. Joe Johnston admits to getting burnt out while working on the film. The film came in on time but it was a lot. Richard Edlund ended up leaving because it wasn’t as fun as in previous years. As Chrissie England notes, the infrastructure was still the same. Even with the staff changes, there was no company that Spielberg trusted more for VFX.

Joe Johnston wanted to quit, take off for a year and tour the world. George Lucas asked him if he thought about film school. Working at ILM was basically going through film school. In any event. Lucas covered Johnston’s education while keeping him at half-salary. All of this would pave the way for Johnston to direct Honey, I Shrunk the Kids. Johnston’s story segues into John Knoll discussing his first foray at ILM. Lorne Peterson gave him a tour of the place. Knoll was only 15 years old at the time in 1978 and the tour blew his mind. “When you see them in person, it’s a lot easier to imagine,” Knoll says. He went to USC because Lucas went to USC.

When Knoll saw what people could do with digital technology, he admitted then and there to seeing the future. Lucas even knew that the future was digital. Sound designer Ben Burtt admits to being naïve when Lucas discussed his thoughts on the future of filmmaking. He would later come around to understand why Lucas wanted to push further into the world of digital. As the fourth part comes to an end, we’re just beginning to touch on the beginning of Pixar. John Knoll also discusses the invention of the technology that would become Photoshop. He created it with his brother, Thomas.

ILM’s computer division, the Graphics Group, would be sold off to Apple’s Steve Jobs and become the Pixar Animation Studios. This is a group that came about because George Lucas wanted to push editing into the digital era. In order to do this, he needed the right people to create the technology. Enter Ed Catmull in 1979 to help ILM with computer graphics, video editing, and digital audio. The rest is history. Catmull’s belief at this point was that a digitally animated film was about ten years down the road. He and Lucas both had a difference of visions for what Pixar could be. After selling the division, ILM would only rebuild and push the use of digital technology even further. Disney acquired Pixar in 2006 and Lucasfilm in 2012.

Part five really delves into the computer graphics side of things. The bulk of this episode touches on Willow, The Abyss, T2, and Ghostbusters II. Prior to ILM working on The Abyss, the only fully-integrated character was in Young Sherlock Holmes. It’s during this time that Jim Morris, Steve “Spaz” Williams and Mark Dippé start working at the company. Pixar may have been sold off at this point but the Lucasfilm still had the equipment on hand. If not for Knoll’s involvement with Photoshop, The Abyss might not turn out as it did. The Abyss would be one of the biggest game changers when it came to CGI filmmaking. Dennis Muren saw the future and it was CGI.

With more and more people realizing that CGI was the future, the model shop employees felt threatened. The future in digital is what brought Ellen Poon to ILM. Doug Chiang eventually came over to ILM, where he became a visual effects art director. These days, it’s hard to find a Star Wars project that Doug Chiang hasn’t touched. But even with the model shop feeling threatened, filmmakers like James Cameron still felt the importance of practical effects for T2.

As part 5 comes to an end, Jurassic Park is looming right around the corner. Remember the comment from Jurassic Park? “They’re going to put us out of a job.” You can really feel it because Jurassic Park had shown that the future was in digital.

Per Kathleen Kennedy, they convinced Stan Winston, Dennis Muren, Phil Tippett, Michael Lantieri, and ILM to work together. Phil Tippett had ONE JOB. But seriously, they were going to go the stop-motion route and then CGI changed the game. Dennis was reluctant to go that route but once they did, you know what happens next. Both Steve “Spaz” Williams and Mark Dippé gave it a shot and managed to animate a walking dinosaur. Phil was also making solid progress with stop-motion raptors. Per Mark, Phil didn’t believe in the computers at this point. There was a competition and you can feel it coming across the screen. During a test screening of a CGI T-rex walking across the screen, the common consensus was that visual effects would never be the same.

To be a fly in the room when Dennis Muren, Phil Tippett, Steven Spielberg, and Kathleen Kennedy saw the test footage. For Spielberg, he knew it as the moment when the world would change forever. Not just his own film but filmmaking in general. You feel sorry for a stop-motion guy like Phil Tippett. When Spielberg asked Tippett how he felt, he commented, “I feel extinct.” Spielberg decided to put a variation of the line in the film after they approach the visitor’s center.

Ellie Sattler: So, what are you thinking?

Alan Grant: We’re out of a job.

Ian Malcolm: Don’t you mean extinct?

Phil Tippett directed the animatics and the live-action dinosaur scenes such as in the kitchen. Even though they didn’t go forward with stop-motion, the final product looks very similar to the stop-motion animatics. I’ve made no shortage of comments about how much Jurassic Park and Star Wars changed my life.

People thought the transition would take longer from practical to digital. Many people in the model shop just packed up their bags and left. If they thought the digital work on Jurassic Park was a lot, Casper would really take it even further. Computer graphics would impact Jumanji, The Mask, Forrest Gump, and more. The changes happened so quickly that George Lucas felt that he could finally make the Star Wars prequels. Stepping in as the design artist was Doug Chiang. John Knoll, Dennis Muren, and Scott Squires were among the VFX supervisors.

Barry Jenkins was working at an AMC when the prequels came out. He would just stop what he was doing whenever he walked into the auditorium. I’ll just say that I’m right there with his comments on seeing Yoda fighting with a lightsaber: “It was just epic.” He’s not wrong. Even though practical Yoda is preferred to digital Yoda, seeing what Yoda could do digitally with a lightsaber was something that could only be done digitally. The prequels might get a bad wrap but they pushed digital technology to its limits in the early 21st century. Jenkins later approached ILM when he was working on The Underground Railroad. Jenkins just smiles when people point out how few visual effects there all. It’s a credit to the work at ILM when you can’t even tell the difference.

Both Jon Favreau and Hal Hickel discuss their work on Iron Man. Robert Downey Jr. was basically wearing pajamas for what would become the VFX shots. You could have fooled me! They fooled Favreau, too, because he couldn’t tell the difference between the CG suit and the practical suit. We later catch up to present day with the technology in The Mandalorian. The technology that they created is just impressive. Deborah Chow was a quick learner, much thanks to the controllers being similar to PlayStation. But anyway, The Volume is requiring a lot of VFX shots upfront rather than waiting months to add them in later. It’s changing filmmaking, again, for the better.

The changes went beyond ILM as a result of the prequels because their work would change filmmaking. Everything we know about blockbuster filmmaking today owes something to George Lucas and ILM. Without their innovations, who knows where we would be today. Even now, ILM is still being innovative with their work on The Mandalorian. The same technology was also used for films like The Batman with the virtual backgrounds.

Anyone going into this doc series with the thought that Lucasfilm is acknowledging the original trilogy as released is reading too much into this. Why would they make a documentary about ILM and not use the original footage from it’s release? Chances are likely that this is the only time you’ll ever see footage from the theatrical release in the years to come. I cannot blame George Lucas for wanting to improve on the films after Jurassic Park proved that the technology was now there. Without Jurassic Park, you can argue that we would not get the special editions or the prequels. Listen, I could use this to segue into a discussion about director’s cuts but that’s another article.

The six episodes run 58, 52, 1:01, 1:01, 52, and 1:02 minutes, respectively. It’s a 346-minute (5:46) journey but every minute is worth it as we travel throughout Hollywood history. Watching this deep dive is just one of many reasons why I enjoy watching bonus features (shoutout to Laurent Bouzereau) when films get released on home video. I love getting to go behind the scenes and see how they put it together. This is one of the things that I don’t like about streaming. They rarely release bonus documentaries. Even nowadays, the bonus docs that should be on the Marvel home releases end up getting held for release on Disney+.

Disney+ delivers again because Light & Magic is one of the best documentary series of the year and there’s so much rich history for cinephiles to digest. The doc series allows us to get to know so many people in a new perspective. They are so much more than just a name during the opening titles or end credits.

DIRECTOR: Lawrence Kasdan

FEATURING: J.J. Abrams, Jean Bolte, Rob Bredow, Lynwen Brennan, Ben Burtt, James Cameron, Ed Catmull, Doug Chiang, Deborah Chow, Mark Dippé, Rose Duignan, John Dykstra, Richard Edlund, Harrison Ellenshaw, Chrissie England, Jon Favreau, John Goodson, Roger Guyett, Hal Hickel, Paul Hirsch, Ron Howard, Barry Jenkins, Joe Johnston, Kathleen Kennedy, John Knoll, George Lucas, Frank Marshall, Jim Morris, Dennis Muren, Lorne Peterson, Ellen Poon, Ken Ralston, Rachel Rose, Kim Smith, Steven Spielberg, Phil Tippett, Steve “Spaz” Williams, Robert Zemeckis

Disney+ will launch Light & Magic on July 27, 2022. Grade: 5/5

Please subscribe to Solzy at the Movies on Substack.