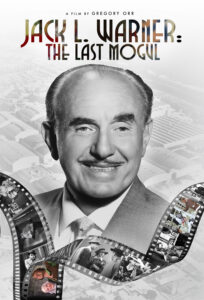

Gregory Orr spoke with Solzy at the Movies ahead of the TCM premiere of Jack L. Warner: The Last Mogul on Sunday, April 2.

Sunday night’s 9:45 PM ET broadcast premiere is the first of two airings in April in honor of Warner Brothers celebrating their 100th anniversary. The next WB100 airing of the documentary will take place on April 10 at 11:15 AM ET. Vision Films will release the film digitally on May 9, 2023, followed by a DVD release.

It’s so nice to speak with you.

Gregory Orr: And you, thank you.

How are you doing?

Gregory Orr: I’m good. Things are getting a little busy with the promotion. We finished the film for Turner Classic broadcast’s on Sunday, but we still have to do a 5.1 mix. There was some footage I was swapping out so we still have some loose ends in the next two weeks we’re tying up. It’s been a long road so I’m glad we’re nearing the end.

What led you to go back and update the documentary in HD?

Gregory Orr: Well, for years, I thought the film—even though it played overseas and had a foreign distributor—it was never sold in the US. Warner Brothers picked up a short version of it as a DVD extra when they released Casablanca in Blu-ray in 2008 but it never had played for US audience. I said this thing is, it’s an interesting take. It’s got unique interviews. I really should do something with it. In many ways, I felt that the original film was more of an outline for an unfinished movie. I’ve thought for years, well, I should go back and, at the very least, up-res everything into high definition but I said no, I don’t want to do that. I want the most pristine footage I can get so let me go back to original sources, original negatives, and finally decided on 4K scan as opposed to just HD scan. In that process, I just looked into it and then with Warner’s celebrating its 100th anniversary—back over the summer, I said okay, if it’s ever going to be done, this is the year to do it. Let me get some money together and approach Warner Brothers about cooperating, giving me updated clips.

The original editor and I started down a path of saying what can we do with this film. As we got into it, we realized we had to do a lot to make this film what it needs to be today and that included footage and a little change in sensibilities stressing different things. We didn’t do a new voiceover but we cut down certain things, changed the focus, added more visuals to help explain different parts, including the business side of it, which was very lacking in the original production—how the Warner Brothers succeed, where they get their money, what kind of money we’re talking about, what do they do, they bought theaters, they bought other businesses, etc. It really was a bit of a reimagining of the original film. I wanted the story to be useful in the sense of—we didn’t even have a deal for broadcast. We started off on this. Nobody said they wanted it but I wanted it to be ready for an archive somewhere film students and whomever down the road could watch this find value in it.

Yeah. One of the first things I did during the at the start of the pandemic really was just load up on all these books of the early studio moguls to see how they responded to the flu epidemic and barely any book mentioned the thing about it. I just read straight through The Brothers Warner and then watched that documentary shortly thereafter. In 2020, I pretty much programmed an entire Warner Brothers week for the anniversary that year.

Gregory Orr: Wow. I understand that you really love Casablanca. Is that true? Is that a film that really speaks to you?

It’s one of the greatest films ever made.

Gregory Orr: I won’t say it’s a mistake, but it is the studio system at its best and everything falling into place. All the supporting actors had been playing some version of that role so they were really good at what they had to contribute. I think that the war with Europe coming up just gave it an emotional resonance to everybody working on it, but this film was about something real big and important.

You had all these immigrants working on that project—Michael Curtiz himself came over.

Gregory Orr: Emotionally, they were connected to what was going on in Europe. I know they rushed it in the release, because there was a conference in Casablanca and Warner wanted to take advantage of that press—the Allied Powers meeting in Casablanca and so they pushed it forward. My mother is in it, too. She told me a story that she read the script before it went into production as she often would. She thought it was very corny, she thought was like, this is like an old-fashioned corny movie. When she heard that, that Ingrid Bergman was going to be in it, she said, Oh, she always brings a lot of class to something so maybe it will be much better. But her first view is like it’s a little old-fashioned. It’s a funny, temporary view.

And then your father is in the film that got MGM kicked out of Germany!

Gregory Orr: Absolutely. He said when they were making that, that someone from the front office came down and said you can’t use that song. They were using some German song and everyone was like, What are you talking about? We’re about to go to war with Germany. What are you, nuts?!? I think they may have swapped out the song that they were originally using. The front office was scared about repercussions at the time in Germany. But yeah, that’s a good movie. That’s a very good movie, The Mortal Storm.

One of four team-ups with James Stewart and Margaret Sullavan.

Gregory Orr: Right. Yeah, it’s interesting, the whole system. I learned a lot more while making this film, doing this update. I grew up in a setting where I’d heard lots of stories but I heard them from people who were on the studio side of the equation, who would tell stories about actors or directors and how people were messing up, this guy was prompted and that’s the problem here. It was all from a front-office view of moviemaking. As time went on, I realized that wait a second, we’re dealing with creative people and artists and they want to do something special and they have to push against the front office. I got to be able to have another perspective as I got into this more and more. There’s still more to learn. There is a new book coming out about the Warner Brothers by a guy named Chris Yogerst out of Wisconsin. He’s done a big book on the history of the studio.

It’s currently in my pile along with the official book for the centennial by Mark A. Viera. Chris and I have gone back for a while now. I read Hollywood Hates Hitler! during the pandemic.

Gregory Orr: That’s great. Yeah, he’s a very nice guy. Tom Doherty recommended I talked to him. I guess Chris recommended I talk to you or you heard about just on your own?

I think I mentioned the documentary offhand and he had mentioned that he had chatted with you, something like that.

Gregory Orr: Okay.

I emailed TCM and they didn’t know if there would be screeners. At the time, it was definitely to clear up confusion, because I’m looking at one thing—TCM has it airing for a two hour block, which I assume some will be an interstitial. And then, of course, the Casablanca anniversary edition—it’s an almost an hour long. I’m like, Wait, is this the same film? Is this a new film? What’s going on here?

Gregory Orr: You’re right. They had the old release date of 1993. I corrected them. I said, we’re having a new copyright on this film and I’m considering it a serious update and a new version, especially because of the amount of visual material and sensibility. We have a whole new soundtrack, new music recorded, new mixes, and a reimagining, in many places, in how to tell their story. They finally said, Oh, okay, we understand. They’re going to change that date to 2023. I’m not denying that it’s based on earlier and all those interviews, obviously, were from the earlier film. A lot of stuff in between has changed.

So yeah, TCM is not doing any publicity for the film, individually. It’s interesting that my distributor doesn’t want to do any publicity for the TCM broadcast either because they said, VOD really doesn’t like it. All the VOD platforms don’t like it if you put your program on free TV. Therefore, they don’t feel their special if you’ve already had a showing. It’s a little tricky there about how much publicity I should do, how much they want me to do. I’ll do some social media. I’d love for it to be reviewed. If anyone wants to talk about it, I’m open for it. We’re not banging the drum too loudly until later in April. It’ll be available through VOD on May 9.

In the film, you mention the time Jack was driving the car and the cop letting him off with a warning. When did you really realize just who your grandfather was as a founder of Hollywood?

Gregory Orr: Well, I always grew up hearing stories and I got to go to the studio, not as often as I want to. I loved going the studio. My father worked there in television, running the TV departments. We weren’t allowed to go too often but I could sit all day and watch movies being made. I knew that this is a movie guy and I didn’t have anything to compare it to in terms of the other movie guys. It wasn’t really until I got into my teens and my friends would ask about it—my grandfather was retiring, was stepping back—that I saw a passing of a generation. I would tell people who were film students or filmmakers, I said, you fell in love with movies watching them. I fell in love with movies watching them being made. I watched stuff on television but I was not a big movie buff. I was up to a point—there were certain movies I really loved. I wasn’t devouring movies every day after school. I came to it from a different point of view so it took me a while to catch up and start to see a lot of movies that contemporary filmmakers and so forth that just grew up on. I watch more television maybe than movies, that sensibilities.

It was somewhere in my high school years, it started to hit me, the impact of this, and what these movies were. Even now, more recently, the whole social relevance part of it, and the way they treated real issues, the more I read, the more I come to appreciate that Warner Brothers really looked at social issues, wanted to say something about them while entertaining. A lot of that’s Harry but Jack’s sensibility, too. If something’s fast—you really want to movies cut fast and this is one big contribution. He only had a sixth grade education. He was not a fast reader and so if you can’t read it, it was too long for the toilet, it’s too long. His major impact was, besides for who would be in it, I think in the editing. He spent a lot of time with the editor watching these movies and time with editors on the trailers and advertising them. Editing is really where I could see the biggest impact on individual films. Move it along.

My father remembers very clearly how Jack would say, what, we don’t need this shot here or just get him in the door. You don’t need to see him walk up the stairs, just move it, move it, move it. There is a sense of rapid impulsiveness, drive in Jack’s approach and the whole studio had it, too, in its way. It’s a factory and they get to churn out these things. What’s the format? I think they start to understand pretty fast that you’ve got to make it impactful and quick and headlines. Warner Brothers movies is filled with the printed word. I think some of the writers and producers came out of journalism. I think they were comfortable seeing a headline and they use that to very good effect in movies in explaining very quickly with some words, what would take much longer in a scene or other plot device.

One thing I really love and appreciate about those early years of Warner Bros. is taking that fight against Hitler and Nazism on the big screen at a time when no one else was really willing to do it.

Gregory Orr: That’s my understanding is that there was a lot of—Neal Gabler talks about this and others do, too—the fear of being too Jewish and being too Jewish-centric with their concern about what was happening in Europe. Every studio heads would have meetings, Motion Picture associations would talk about these subjects and, like it’s going to not only ruin our business, it’s going to get us in trouble with antisemitism in the US. So walking a fine line, but I think Harry was a big champion of that. People in the studio, I think, would ask them about it, too—some of the directors were European. It was certainly in the air, like, what do we do about this as they read the paper every day. I think it made it easier for them once Confessions of a Nazi Spy that it’s a true story that this was something that okay, we found Nazi spies in the US, that’s not a Jewish issue but we were able to address Nazism through this real trial.

They were able to bypass Joseph Breen’s strict enforcement, if I recall correctly.

Gregory Orr: You’re right. There’s a lot of letters in the USC files and maybe Wisconsin, too. Jack was pushing back against censorship and these things. There’s constant letters about why it’s important to show these things and do these things, a reframing the argument. He didn’t make individual movies so much, except when it came to general casting, editing, and making sure they kept to the schedule. As a side note, people told me that he’d just decide when they shot enough. He’d been watching watch the dailies every day so he’d see what film was being done and say, You know what, tomorrow is gonna be their last day. Even if they had an extra week or three days on the on the schedule, he’d say, We’ve shot enough, that’s it. He’d just say, you’re finishing tomorrow, figure it out. That’s sort of the bottom line part of it but his job was to make sure the studio was being efficient and if the salespeople in New York were doing their job and that whatever hassles were coming his way, from the Catholic League of Decency, the Breen office, the Hayes office before, was being managed, so they could do what they wanted to do. And of course, contracts with actors and things like that. But yeah, he was sort of like, he wasn’t the coach of the baseball team, he was the manager.

What do you think Jack and his brothers would think about the current makeup of Hollywood with the conglomerates and rise of streaming services?

Gregory Orr: Well, my father said that Jack appreciated television in terms of making money, but he didn’t like the medium. He really was a movie guy. He liked the movie theater and he liked live theater, too. He’d go to see a lot of plays in New York when he came back. When he was young, he did vaudeville so something in the theater is what was comfortable in. My father says he never watched any of the TV shows that Warner Bros. was making before they went on to the station. My father would say, Okay, we got we got the pilot for the show and when do you want to see it? My grandfather would say, Well, okay, next week and finally, Jack would say, Okay, I’m ready to see the pilot. My father would say it’s too late. It’s already been shipped to the network so you missed it, Chief.

Today, I think would they understand it all? I know, my grandpa didn’t particularly like lawyers and agents—they made his life more complicated and took away some of those power. He’d complain like an older guy and understand the new system but it is a different system and different pressures. Movies started off as a fad, as a craze. When they got into an industry, people in the beginning were willing to see anything. It was the only game in town in terms of visual entertainment except for a live show. We just went to the movies. That’s how you get out of the house, for a nickel or 25 cents. They were able to ride that phrase for quite a while.

As audiences became more sophisticated, the movies had to change. They understood that. Jack wrote about that at some point that they’ve get to change or their audience, they understand more. Our movies have to address that, too. As he got into his later years, he complained about the agents and the lawyers, the kind of movies that (inaudible) of their day.

I give him credit for hanging in there as long as he did, greenlighting a movie like Bonnie and Clyde that he didn’t fully understand, Warren Beatty said. It seemed like an okay deal. Though he never understood why someone would want to make a gangster movie in the 60s and felt that the genre is dead. I don’t think he ever understood why Warren Beatty wanted to make it. He allowed talented people to go ahead and do what they wanted to do. Even if he told him not to, there’re lots of memos out to say nobody listens to me. I told them don’t do this, but they’re doing it anyway—(laughs) That’s very funny like a parent whose children are off doing what they want to do, a little exasperated. He liked talented people and he was willing to get people in who would disagree with him. But if they had talent and box office success, that was fine with him. He hated 3D movies until he saw what the first one was making in the box office and he said, Okay, we have to make a 3D movie. He was running a business interest along with being a moviemaker.

I’m actually meeting one of the stars of one of the final films he produced when I go to C2E2 on Friday.

Gregory Orr: Who are you going to go see?

Gregory Orr: Oh, sure. That’s great. Wow. There’s a story that I’m told that my grandfather didn’t know who’s gonna direct the movie. He liked the play. He bought the play 1776 but someone finally asked at the press conference, who’s going to direct this? My grandpa just blurted out, well, the guy who directed it can direct it. It’s just like one of these decisions without much thought behind it. Peter Hunt—for first time director. I thought he did an okay job. Would a more experienced hand have reshaped that story a little differently? Perhaps. He would just blurt out things just to get it moving. I’m told that he never said Ronald Reagan should be in Casablanca. He may have said that to someone just to get them moving. They were taking their time casting that movie, if I understand from my father, and he might have blurted out, We’ll just put Reagan in it. That goosed everybody to get somebody more appropriate. Yeah, he worked by instinct in a way. He said once my father was there, he said, I used to be able to sit in the barber chair and cast the movie. He knew all the players, he knew everybody. You get older, you get new people, and you just don’t know them anymore. You’re on shaky ground on what to trust.

What do you hope people take away from watching the documentary?

Gregory Orr: I think an appreciation that there were a group of people who created not only the reality of the idea, the American movie industry and the kinds of films they made. There was nothing before. It’s just fallow ground. It’s a wheat field and people came in and started building an industry and churned out stories, and had to get technology up and running—the distribution systems, the publicity, and the whole idea of movie stars. Europe didn’t have that, initially—it was the directors, maybe, and the films themselves—the star system being developed in the US so the whole idea of change and development was so incredible. It sort of matches what happened to computer rates now, maybe even faster.

1927 is the first talking movie. In 1939, it’s the big color epics like Gone with the Wind in such a short period of time. In 12 years, you go from the first talking to these big, giant movies. They did that. They kept making it up as they went along and fortunately, they had an audience who was hungry for it. But they definitely had to adapt. There was constant adaptation. Some problem came in, somebody got tired of this. You don’t do the gangster movies anymore. You don’t use these musicals anymore. You have to do something else. It’s not like they just made a product that they could keep remaking for 20 years. They had to keep coming up with new models.

I think understanding that maybe helps filmmakers today in imagining, well, what, what does the audience want? What does the audience need? And can we even anticipate giving the audience something they don’t even know they need? I suppose you could say that about Avatar. I was there at one of the first screenings of Star Wars. I was in college at the time. I had friends at CalArts. I had friends who were working on Star Wars and it’s all very top secret. They were doing very simple rotoscoping—drawing out certain things had to be replaced with special effects, almost like cartoon cel animation, frame by frame, they were doing this simple work. I heard about this and I went to an early screening, and the audience just erupted as if all their childhood fantasies reading comic books, space adventure books, and all that had come true on the big screen. They didn’t even know they needed a movie like this but there it was.

Avatar maybe has some of that same realization for audiences. I know their audiences didn’t want to leave the theater; they were disappointed going out into the real world. Movies, at their best, give people an organized experience that touches you so deeply, you didn’t even know that you needed it. I think that’s how movies will survive as a valuable art form and form of entertainment. Fortunately, it attracts smart and talented people, attracts crazy people, too, but it does attract enough people who have a vision and want to use the medium to say something. I agree.

Also, with video games, I don’t know if that changes people’s sense of storytelling of what they want out of a movie. Movies are so linear now for people who play video games. They don’t see things in theaters as much and have a different relationship. It’s not big anymore. It’s just the size of the TV show—your screen. But listen, it is a new art form. Someone said, it’s an original American art form created at the end of the 19th century, beginning of the 20th century, and we’ll see if this art form, this language of visual storytelling cinema will endure, that people will want just not talking heads, like a stage play, but something different as so called cinema has. I hope so because it is an exciting art form. That means people need to at least acknowledge what silent cinema did and what other movies have done since then in how they tell stories and does it give pleasure in seeing stories told that way. I hope so. I hope so.

Yeah. I’m hoping that these theaters are able to stay in business, because I know a lot of closed because of the pandemic.

Gregory Orr: As you know, it’s the event movie that gets people in and the big, big movie. I want to see that too. I mean, I’m not a big Marvel fan, I was never a Marvel fan. I didn’t read those tiny books. I was more of a DC guy. I’ll go see them because they’re big spectacles and I want to see how the spectacle is done on a big screen. But, again, it’ll pivot. Who knows what the audience will need—something else—I mean, in three years time, if we go to war with China, or the economy tanks or who knows, people will want stories that reflect what’s on their mind, and what concerns them and what they want answers to. Hopefully, movies can keep providing some relief, entertainment, and an insight into the world we live in more than just a TV series. I don’t know. I’m hopeful that the visual medium will continue in some way. Listen, I’m thankful for people like you—the younger generation who somehow the magic, something about it pulled at you and you responded because that partly keeps the heritage alive, too. The movies we’re into now is part of a long process.

Yeah. Thank you so much for your time. It was nice getting to chat with you this afternoon.

Gregory Orr: Thank you. Listen, Danielle, I really appreciate you taking the interest, I do.

TCM will broadcast Jack L. Warner: The Last Mogul on April 2, 2023 at 9:45 PM ET and April 10 at 11:15 AM ET. Vision Films will release the the film on Digital/VOD on May 9, 2023.

Please subscribe to Solzy at the Movies on Substack.