Nim Shapira opens up about TORN: The Israel-Palestine Poster War on NYC Streets and how his feature debut confronts division and empathy.

In our conversation, filmmaker Nim Shapira reflects on the making of his debut feature TORN. He discusses how the film emerged from grief and fractured communities after October 7, why he sought out messy, contradictory voices, and how he captured the fleeting yet volatile poster war as a cultural time capsule. Shapira also speaks candidly about the emotional toll of working with such charged material, the unpredictable reactions from audiences, and his belief that discomfort and disagreement are essential steps toward dialogue and empathy.

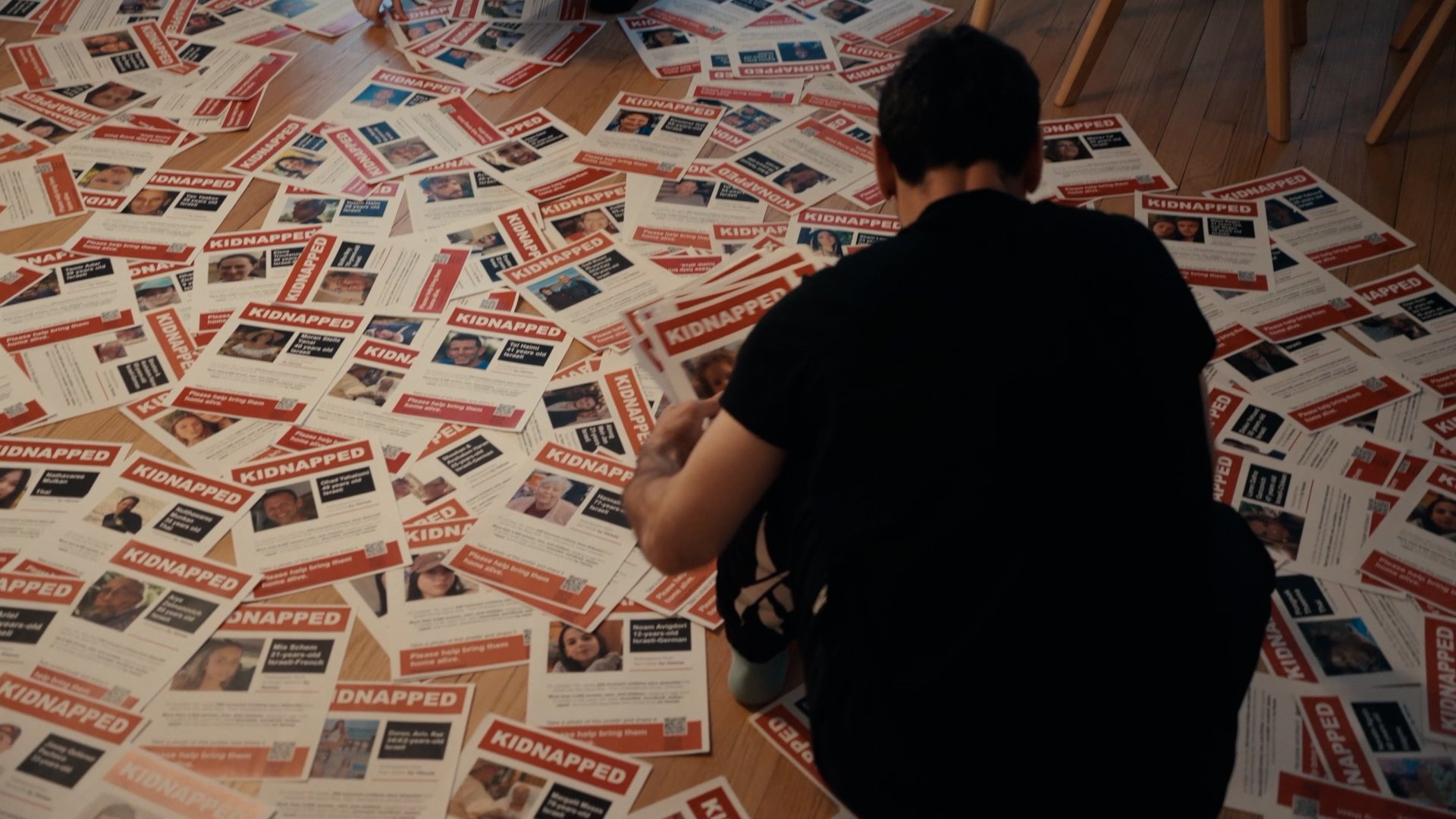

In the wake of the October 7 Hamas attacks, TORN follows how a grassroots poster campaign for 251 hostages spiraled into a symbolic street battle across New York City. What began as a call for compassion soon became a clash of narratives, with pro-Israel and pro-Palestine activists tearing down each other’s posters and contesting public space. Through the voices of ten New Yorkers—including hostage relatives, students, artists, activists, a rabbi, and a free speech advocate—the film captures a moment of grief, identity struggles, and the fragile boundaries of empathy. Shapira’s documentary asks not for agreement, but for the courage to confront complexity in a divided time.

Following its festival run, TORN will open in New York beginning this Friday and an LA release will follow on September 12. The film will expand to additional cities and a digital release is expected for later this year.

It’s so nice chatting with you today. How are you doing?

Nim Shapira: Thank you. It’s a beautiful autumn day in New York, and in theory I should be celebrating my first feature release. But it’s hard to feel joy when we’re nearing 700 days of war—with 48 hostages still held in Gaza, a humanitarian crisis unfolding, and tens of thousands of innocent Israeli and Palestinian lives lost. For me, TORN became a way to channel helplessness into something tangible. I can’t change events overseas, but I can shape conversations here, in the city I’ve called home for 12 years. That sense of purpose is what keeps me going.

Torn has been playing the festival circuit for a while now. How relieving is it to finally open the film theatrically for a wider audience?

Nim Shapira: “Relief” isn’t quite the word—it actually feels more stressful. At festivals and special screenings, audiences arrive ready to engage. A theatrical run is different: complete strangers with wildly different backgrounds sit together in the dark. That was always the goal. Opening first in New York—the city that inspired and shaped the film—feels right. It’s not relief, but it is purpose. And honestly, if New Yorkers can sit through it together, maybe there’s hope the rest of us can too.

What was the genesis behind making the documentary?

Nim Shapira: I resisted at first—it felt too raw, too close. After October 7, even my own circle fractured. Friends unfollowed each other, skipped gatherings; college students I know were ostracized. The city felt split down the middle. TORN became my way of saying: we don’t have to agree on each other’s narratives, but we do need to listen.

I was also struck by impermanence: paper fades, rain and snow wash posters away, but the emotions they unleashed will outlast them. I wanted to capture that fleeting winter of 2023 as a kind of time capsule, and to wrestle with my own questions. The film doesn’t hand out answers; it asks them. Sometimes asking is the most radical act you can do.

How did you decide who to interview for the film?

Nim Shapira: I wanted voices that feel like New York: messy, contradictory, alive. I spoke with dozens of people and focused on ten—hostage families, students, activists, a free-speech advocate, a rabbi, and individuals that were doxxed for tearing down posters. Then I layered in commentary from across the spectrum—TV, Twitch streams, viral clips. The goal wasn’t neat balance, but cacophony—the same collision of narratives we all experience scrolling. My hope was that viewers would recognize themselves, or someone they know, in at least one voice.

A number of videos went viral of people tearing down posters. How did you decide which ones to include?

Nim Shapira: I combed the web and cataloged every video of ripping I could find and chose for range: campus confrontations, “quiet” removals, shouting matches, even moments that turned violent. I wanted to show not just Jews and Muslims interacting, but the surprising diversity—across age, race, and background—of people who tore the posters down. I also kept in the reasons people gave on camera. For some, these weren’t faces of kidnapped children; they were symbols of “propaganda.” Once you stop seeing a person, it’s easier to erase them. That dehumanization is part of the story. And in a way, the act of erasure became its own character in the film.

This was your first feature-length film. What was the most challenging aspect of the making the film?

Nim Shapira: Emotional stamina. Watching your city descend into rage is one thing; editing those images every day is another. There was so much hate and anger in each video I sourced. Timeliness was also a challenge—headlines kept shifting. The trick was to make something urgent enough for this moment, yet lasting enough to matter beyond it. The challenge wasn’t just technical; it was human. How do you stay open-hearted while staring at division all day? That was the hardest part.

The final runtime is 75 minutes long. How long was the rough assembly cut?

Nim Shapira: Well over two hours. Each interview ran around four hours, so cutting was excruciating. But it forced me to distill the essence: how the poster war exposed the fragility of empathy, the fight over free speech, and the question of who belongs. I wanted people with no personal ties to Israel or Gaza to see not just politics, but people. That was the essence. If I had to boil it down to one rule: cut everything except what makes you feel something.

Were there things that you thought about including but couldn’t find the right place?

Nim Shapira: My original vision was to end with the artists behind the posters—Dede Bandaid and Nitzan Mintz—tearing them down but not out of anger and erasure but because all the hostages had come home. Tragically, that hasn’t happened. They are still held captive.

Were you surprised that the people who tore down the kidnapped hostage posters declined to be interviewed?

Nim Shapira: More saddened than surprised. I reached out in every way I could—emails, DMs, even through their GoFundMe pages—some said they already said everything there is to be said and others chose not to respond. Still, I felt their perspective had to be part of the film. So I found a creative way to weave it in without direct interviews, and audiences have praised me for how I executed it—that it feels both empathetic and inventive.

What has the reception been like as you’ve attended screenings during the past year?

Nim Shapira: We’ve now screened TORN more than 70 times—from Miami to Seattle, in film festivals, interfaith communities, Ivy League universities, community centers, private homes, and rented theaters. Each screening has been completely different, with its own set of questions and conversations. I’ve been grateful to connect with people from such diverse backgrounds—international students, academics, Middle Eastern immigrants from places like Jordan and Egypt, audiences from South America and Asia, and American Jews across the political spectrum.

A lot of people told me they were deeply moved by the film but didn’t like one or two scenes—and the fascinating part is, it was always a different scene. That tells me the film made people think, made them uncomfortable, and that’s exactly what I hoped for. TORN is built on the belief that multiple truths can exist at the same time. If the film makes you stop and wrestle with that complexity, then I’ve done my job. I’m not looking to preach to the choir—there’s already enough of that on both sides.

Documentaries dealing with October 7 have had a tough time finding distribution in the United States. Did you ever worry about finding distribution?

Nim Shapira: Of course—it’s polarizing, and distributors know that. Some festivals and cinemas even told us privately that they were afraid of protests, boycotts, or the impact on their insurance. I can understand that fear, but it’s still very sad. At the same time, we were fortunate to find partners who believed in the film: Hemdale Films, GATHR, and PBS International. I’m proud the film found its place. The very fact that fear dictates programming shows why this film needed to be made.

The world has become so divided during the past two years to the point where there are massive protests against the inclusion of Israeli artists, actors, filmmakers, not to mention Jews in general. When this war comes to an end, do you think there will ever be healing or do you see this surge of antisemitism growing worse?

Nim Shapira: Criticism of Israel’s government is not only fair—it’s necessary. Israelis themselves fill the streets demanding an end to the war and the release of the hostages. But turning that anger into hostility toward Jews everywhere is something else entirely. Treating all Jews as complicit flattens our voices, erases our diversity, and that is antisemitism.

Boycotting and silencing aren’t the answer—and the film shows that this happens on the other side too, to pro-Palestinian voices. Art is supposed to reflect society, act as a mirror, and provoke thought. Israeli and Jewish art has always been deeply self-critical—we practically invented arguing with ourselves. Silencing those voices achieves the opposite of progress.

Antisemitism—like Islamophobia, racism, or Asian hate—is never just a “minority problem.” It’s a problem for the entire society that tolerates it.

What do you hope people take away from watching the film?

Nim Shapira: That disagreement isn’t failure. If the film made you uncomfortable, if you argued, if you questioned yourself—it did its job. The challenge is learning to hold two truths at the same time, however painful. And if TORN leaves you with more questions than answers, then I think it’s done what art is meant to do.

Hemdale Films will release TORN: The Israel-Palestine Poster War on NYC Streets in NY on September 5, 2025, and LA on September 12. Additional cities and a digital release will follow.

Please subscribe to Solzy on Buttondown and visit Dugout Dirt.